This week has been filled with news of a Chinese balloon flying at 60,000 feet over the United States and it has begun to cause a mild form of mass hysteria in the public. You can read more about it here: https://www.dailymail.co.uk/news/article-11712125/Explosion-sky-Billings-Montana-Chinese-balloon-spotted-U-S-airspace.html This takes me back to a time in the 1990’s when I was involved in ballooning at the French Space Agency. We were developing balloons for Mars and the analog altitude to fly them on Earth was 120,000 feet. However, as you soon find out, mixing helium and plastic bags is anything but simple.

The latest Chinese balloon incident is unnerving the US public and the federal government as it is flying near operational altitudes of jetliners over the US. It’s down to 60,000 feet altitude and seems to be anything but a rogue balloon if it’s been at this altitude from the beginning. As I found out working with Worldview Enterprises, you can use steering winds at these altitudes to make the balloon go mostly here you want it to go. This takes active control and is not the behavior of the so called rogue balloon. Other reports mention that the balloon started at 120,000 feet and there is little opportunity to steer the ballon at this altitude. This, if true, would imply that the balloon is indeed a rogue device without active steering and now simply following the jet stream at lower altitude.

What is ironic is that these devices are very difficult to take down with conventional weapons. I had this experience during my experiences in France where we had a few rogue balloons. I talk about this in my upcoming book Breaking All The Rules:

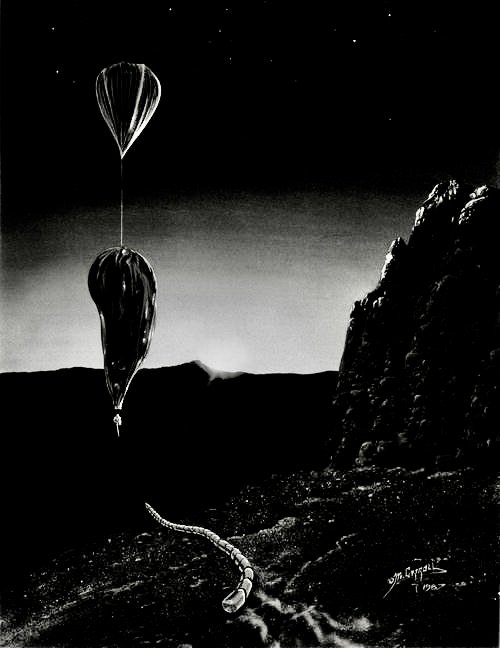

“The summer of 1990 was to be a busy one. We had numerous balloon flight tests planned to validate the basic super pressure balloon, a free flight in the desert to test the SNAKE and balloon system in ground-contacting mode, and a trip to Russia planned to evaluate a SNAKE radar test site in Latvia. As is the tradition in France, nearly the entire country takes the whole month of August off. I found this idea of taking a month off of work to be both very foreign and appealing at the same time. My time frames would not allow it but I still needed to work around everyone else’s schedules. We had planned a desert test in September in the Mojave Desert so I planned to spend my time back in the U.S. after the test catching up with family. Still, we had a lot of preparation for the tests and I had the entire country of France to myself during the month of August and remained at work.

Our first balloon flight tests took place out of a spot called Gap high in the French Alps near the Italian border. This small town permitted us to fly the balloon at 120,000 feet in the atmosphere where the conditions resemble the Mars atmosphere and cut the balloon down west of the site near our other test area at Aire Sur L’Adour in western France. We brought a number of balloon test vehicles along with gondolas that would transmit position and critical balloon performance data back to us. They also accepted commands to deflate the balloon and cause the gondola payload to parachute down to the ground. It was customary to place identifying plaques on the payloads in the rare case that we lost the payloads and in the hope that this would encourage anyone who found it to contact us. In our rush to leave the facilities in Toulouse and make it to Gap, we forgot to mount the identification plaques. As it turns out, I was the only one who brought business cards with me to the test so we decided to put my business cards on the outside of the payloads.

Our first balloon, constituting some 5000 cubic meters and filled with helium, lifted off from Gap early in the morning in July. The ascent was normal and everything appeared to be performing nominally. During this particular time of the year, known as the stratospheric turnaround, the balloons would drift overhead for a period of time and then head slowly west due to the easterly zonal winds at 120,000 feet. This went as planned on the first flight but when we went to cut the balloon down, we lost communication with the gondola. This would normally be a good reason for panic but in this case, the balloon was heading for the open Atlantic and would be expected to be well above any airline traffic. In any case, we could not track it so all we could do was to report this as a rogue balloon to French air traffic controllers. As I was to find out later in my career, the business of a ‘rogue balloon’ was a very big deal to the U.S. Federal Aviation Administration and would revoke your license to fly balloons. In France, the attitude was much more casual and without any noticeable consequences.

Our next balloon flight used a backup of the same equipment and was launched a few days later from Gap. This one performed as expected and remained very close to our target drop location. Unlike the last balloon, when we commanded the gondola to terminate flight, it separated from the balloon and headed down towards the recovery point. The balloon, however, did not self-destruct in the way it was designed and managed to stay aloft. The balloon had a hot wire in the bottom of the balloon fabric that melted the thin Mylar and the deployment of the gondola would tip the balloon upside-down encouraging the helium to empty from the balloon. This did not work as planned. We monitored it for a few hours as it dropped down to about 60,000 feet and wandered north as it encountered the lower atmosphere circulation. Again, we notified the French aviation authorities and again nobody seemed overly excited about this latest failure.

The next day, I took the opportunity to head back to CNES with a colleague who was needing to go back early and go back to work. I was pretty much alone in the project office when the phone rang and our secretary answered the phone. It was from a Colonel in the French Air Force looking to talk to someone about the rogue balloon we had just launched. Apparently, it was menacing the Paris air space floating along at 40,000-50,000 feet. It was still too high to interfere with much air traffic but the angst among aviation officials was high enough that they notified the French Air Force (otherwise known as L’armee de L’air). Annie, our secretary, convinced me to talk to the Colonel and I brought my best French. By this time, my French skills were beginning to be passable but most of what I had learned was from hanging around in the CNES machine shop and talking with the machinists. To say that the majority of my French vocabulary was not meant for polite society would be an understatement. As I spoke on the phone, the limits of my French became immediately apparent and we switched to English. I was surprised to find out that this gentleman wanted advice on how to shoot down the balloon with military aircraft. He informed me that they had sent Mirage fighters to do a fast pass of the balloon on a vertical trajectory and it looked mostly intact. He asked me about using large-caliber bullets and air-to-air missiles to cause the balloon to burst. After a 30-minute-long surreal discussion about shooting down our balloon over one of the most beautiful cities in the world, we parted company. I never found out if they tried to shoot the balloon or just let it drift away.

Our second balloon came back to revisit me later in August. I was again working alone in the office during the month when everyone else would be on vacation. I enjoyed the solitude and the ability to get a lot done without interruptions. A lot of preparations were going on in the U.S. for our balloon tests in the desert later in September and this also gave me more flexible hours to work with my colleagues there in the U.S. eight hours behind us. I was beginning to get used to the rhythm of working quietly at CNES during the day and spending the evenings on the phone at home discussing progress with my U.S. colleagues. When the phone rang in my office late in the afternoon that day, I assumed that it was one of my colleagues from USU working on the SNAKE prototype that we would be testing in a few weeks. When I picked up the phone, the voice was definitely American but this was a Sheriff from Cook County Illinois near Chicago. He was looking to speak with me and explained that he had come across a rather mysterious object that had my business card on it and was trying to figure out how to return it to its rightful owner. As the Sheriff described it, he was called to investigate a large clear plastic bag draped over utility lines on a county road. Once they successfully removed it from the lines, they found the gondola still attached to the balloon along with my business card. I was somewhat horrified but simultaneously amused that the balloon had made it this far yet was found. This was clearly our rogue balloon that disappeared from GAP. The Sheriff mentioned that since this was a French government device, he would box it up and hand it off to the French consulate in Chicago. Some months later we would receive this box along with some stern words and warnings from the embassy officials about not repeating this.”